The soft light of late afternoon

The 20th century and three of its greatest political upheavals are reflected in the program ‹Kontraste› (Contrasts). Samuel Barber's ‹Adagio› became famous through an anti-war film. Edward Elgar's Symphony No. 1 echoes with the dull pomp of the British Empire in decline. And Richard Strauss' ‹Duett Concertino› was composed after World War II while he was in exile in Switzerland.

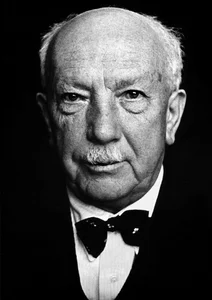

October 28, 1942. The curtain falls at Munich's National Theater after a performance of Richard Strauss' opera Capriccio. It is his fifteenth and final stage work. With this premiere, the composer, who is almost 80 years old, declares his creative work to be over. The most famous opera composer of his time falls silent. What follows now, says Strauss, is of secondary importance. «The notes that I am now scribbling down as a wrist exercise for my estate have no significance in music history.»

The works that follow are bathed in the gentle light of his late period. Sometimes melancholic, as in the Metamorphoses, written on commission from his patron and conductor Paul Sacher. Or as in the unrivalled beauty of the Four Last Songs, completed in 1948 in Pontresina in the canton of Graubünden. On the other hand, the late Strauss also appears cheerful and serene. This is evident in the duet Concertino, or simply Concertino, for clarinet, bassoon and string orchestra with harp, premiered by the Orchestra della Svizzera italiana (now Orchestra della Svizzera italiana).

Switzerland played an important role in Strauss's later life. Initially, he believed he could come to terms with the rulers of Nazi Germany – Strauss was president of the Reich Music Chamber from 1933 to 1935 – and thus exert a positive influence on cultural life in Germany, but this relationship soon turned into the opposite. He was banned from performing, conducting, and traveling. It was only the official invitation to the premiere of Metamorphosen at the Tonhalle Zurich that enabled Strauss to leave the country at the end of 1945.

Contact with Lugano was established through Otmar Nussio, conductor and then program director of Italian-Swiss radio. Nussio invited Strauss to conduct a concert in Lugano on his birthday, June 11, 1947, and persuaded the composer to allow him and his orchestra to premiere the Concertino. The big day arrived on April 4, 1948.

Strauss wrote in a letter that he had taken his inspiration for the Concertino from a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. A dancing princess (the clarinet) is first frightened by a clumsy bear, then the two dance together, and finally the bear is transformed into a prince. This is a brief summary of the symphony's ‹program›. The solo parts in our concert will be played by Italian Rossana Rossignoli, principal clarinetist with the Sinfonieorchester Basel since 2010, and Austrian Benedikt Schobel, principal bassoonist with the orchestra since 2011.

Edward Elgar's marches Pomp and Circumstance enjoy worldwide fame. The first of these five marches, composed between 1901 and 1930, is performed at the popular BBC Proms concerts and is considered Britain's secret national anthem. The ambiguous title can be translated as ‹splendor and pomp› or, depending on the context, ‹pomp and circumstance›. At the beginning of the 20th century, the British Empire reached its greatest extent with colonies on every continent. It was only natural that this power should be reflected in ‹pompous› celebrations.

This was also the case in Elgar's Symphony No. 1, which premiered to frenetic acclaim in Manchester in 1908. The first movement begins with a majestic hymn over a slow, marching rhythm. Elgar writes Nobilmente e semplice here. A contradiction? Not for the music, at any rate. The development builds powerful arcs and repeatedly seeks to retreat into the semplice, with the music seeming to take a run-up to even greater grandeur. Or is it the other way around? Does it reflect, almost with alarm, on a delicate inner life?

Elgar also brings together seemingly incompatible elements in the second movement, where he mixes a whirling scherzo with a march. Similarities with Wagner then emerge in the following adagio. Is it a coincidence that this echoes his Rienzi—an opera about the «last of the tribunes», as the title suggests? In the final movement, the motto that subtly connects the symphony, the hymn from the first movement, reappears. This reprise, even though it is reinforced by figurative notes in the orchestra, has a melancholy quality that is typical of Elgar. Perhaps it is a sense of the vulnerability and fragility of even the strongest-seeming organism.

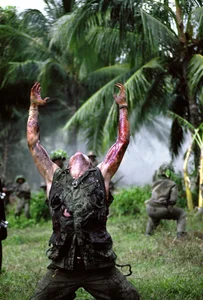

Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings found its way into a political context in a roundabout way. Barber wrote it in 1936 during a summer vacation in the Salzkammergut, originally as the slow middle movement of a string quartet. However, the movement, which is essentially based on a single melodic idea that moves imperceptibly toward a climax, was completely removed from this context by Arturo Toscanini's orchestration for strings. When Oliver Stone then used the Adagio in his anti-war film Platoon, it became pacifist funeral music for the United States, traumatized by the Vietnam War. In a scene at the end of the film, a helicopter takes off over a bombed-out landscape littered with corpses. A soldier's voice is heard off-screen saying, «We weren't fighting the enemy, we were fighting ourselves.»

Author: Benjamin Herzog