Wanderlust, hiking songs and hiking woes

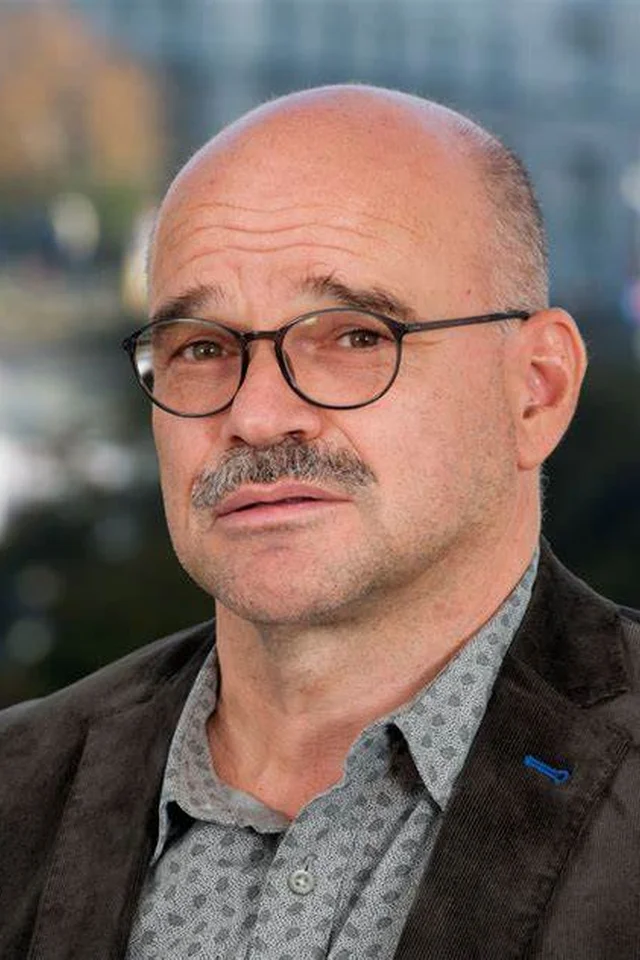

Alexander Honold (born in 1962 in Valdivia, Chile) is a literary scholar and professor of German studies at the University of Basel. He recently published a biography of Hugo von Hofmannsthal entitled Grenzenlose Verwandlung (Boundless Transformation) (S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 2024) in collaboration with Elsbeth Dangel-Pelloquin.

Alexander Honold examines hiking as a cultural motif in literature and music. From romantic hiking songs to symphonic landscape paintings, hiking is revealed as a source of inspiration, an expression of longing, freedom, and existential experience.

Migratory birds do it, clouds in the sky do it, and flowing water knows no bounds in its course; in botany, even everything that has taken root pushes beyond its own location to «seek something else,» as Hölderlin writes in his elegy Der Wanderer (The Wanderer). Humans have learned to wander from nature, so it is no coincidence that even in artistic forms of wanderlust, they are powerfully drawn back to their natural landscape habitat. Gustav Mahler was not the only one known to love composing in the great outdoors, gathering ideas during hours of hiking; for Schubert, Brahms, and later Richard Strauss, walking through the countryside was also a special source of inspiration, with no certainty at the outset as to where it would ultimately lead.

Wandering is one of the oldest forms of movement in history, in which individuals, small groups, or entire peoples set out on a journey. Often they were driven away by difficult or hostile living conditions, and in many cases they were searching for the promised land of a happy future; Some restless souls simply wanted to roam the land in search of new, broader horizons beyond the round curve of the earth. Entire expedition fleets set sail for overseas territories, and brave, determined pilgrims embarked on weeks of arduous journeys on foot to their places of pilgrimage. Despite this millennia-long history, migration as a cultural ideal only really emerged in the last third of the 18th century, when word spread that spiritual edification did not necessarily have to take place in churches and that education could not be imparted solely in classrooms or from lecterns.

«When listening to longer pieces of music, hearing is ‹on the move› in a way that constantly establishes mental connections between the point of departure and the expected destination.»

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, weary of civilization, recommended walking across the countryside, through the Alpine valleys and along the shores of lakes, as a way of experiencing nature that would expose the «promeneur solitaire» to a rollercoaster of emotions and thus stimulate energetic thoughts. And Johann Gottfried Seume, with bold understatement, even undertook a walk to Syracuse to demonstrate that even with a modest travel budget, it was possible to reach the longed-for world of Mediterranean antiquity on foot from cool central Germany.

The Romantic period can be considered the heyday of hiking. Countless hunters and wandering apprentices roam through the poetic worlds of Joseph von Eichendorff, wandering miller's apprentices search for work or wander lonely through Schubert's relevant song cycles, leaving the villages in the bitter winter cold as strangers, just as they had arrived there before. Quite a few of the romantic poems set to music can be traced back to a new poetic development that emerged at the beginning of the 19th century, which in turn arose from the practice of students hiking together from city to city – the genre of the student hiking song. Sung during the hike, and usually also immersed in the scenic ambience of the hike in terms of content, the hiking song marks the emergence of an original vocal genre that incorporates elements of both folk songs and art songs, whose influence on the musical work of several generations of composers in the 19th century can hardly be overestimated.

Poetic, but also in terms of its historical origins, Gustav Mahler's settings of the Wunderhorn poems and orchestral songs still resonate with something of the euphoric exuberance with which student hiking groups swarmed into nature during their lecture-free periods. However, by the time Wilhelm Müller and Franz Schubert's Winterreise came along, the hiking song had become a thoroughly ambivalent form of expression, in which strongly melancholic impulses repeatedly found their way in alongside sanguine departures. And especially in the Biedermeier period, the lively wanderlust of brave Sunday hikers was contrasted with the painful compulsion to wander of the homeless and uprooted as a warning example. The hardship of migrant work and temporary, insecure employment is also familiar to the tailor's apprentice described by Gottfried Keller, who in the novella Kleider machen Leute (Clothes Make the Man) wanders along the country road «on an unfriendly November day» to find new employment in the rich town of Goldach, a few hours' walk from Seldwyla; a journey that, miraculously and unexpectedly, will still lead him to his destination of happiness.

Hiking is a fateful experiment with good and bad paths, as is also known from Schubert's Müllerin cycle, where roads and streams compete with each other to keep the traveler on the right track. The dramaturgy of a risk-prone hike includes the surprises of a winding path with inclines and steep sections, soft or rough surfaces. No one knows in advance which path will be passable under the given weather conditions. That is why, at the end of the 20th century, the French cultural philosopher Michel de Certeau described in his essay on the art of action an ideal-typical contrast between «map» and «hike», in which theory and practice, geographical plan and self-guided terrain are sometimes starkly opposed.

In literature and music, the motif of wandering is exemplary for all those subjects whose representation is based on a linear sequence, so that the first step leads to the next and the next, and what comes later follows successively from what came before. While in classical times many musical forms were primarily based on geometric patterns such as circularity, repetition, and symmetry, the freer, improvisational forms of, for example, the toccata, the fantasia, and later the ballad gave rise to the need to make the compositional design more process-oriented. The aim was to endow the musical course of events with all kinds of unpredictable detours, curves, and obstacles—just like the landscape experience of a hike. In tone poetry beyond the sonata form, as realized in Hector Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique with its basic thematic motif of the idée fixe wandering through five different stages of life, there is a remarkable enrichment of the musical elaboration with narrative patterns from the Bildungsroman or travelogue. Listeners are drawn into a path of destiny that seems to unfold with a consistency modeled on the events of nature.

A sequence of travel stops and landscape impressions runs through Franz Liszt's piano cycle Années de pèlerinage, the first volume of which is based on the composer's trip to Switzerland and leads successively to scenes on Lake Lucerne, Lake Walen, and in Valais. Bedřich Smetana's tone poem Má Vlast also follows the wanderer principle in a different way. In its well-known Moldau section, the initial runs of the flute and clarinet in barcarolle meter tonally depict the bubbling up of those source rivers, whose many individual streams gradually unite to form the great Moldau River. When the Moldau then lets its rousing tonal scale melody flow away in powerful streams, a powerful forward movement takes place in the musical soundscape, creating its own inner landscape filled with melodies.

The tonal and melodic unfolding of the musical event ‹grows› through the imagined landscape of reference into a vividly experiential, three-dimensional event. This is an experience that can be had with many musical works inspired by hiking experiences and modeled after them. Moreover, when listening to longer pieces of music, the listener is also ‹on the move› in a way that constantly establishes mental connections between the place of departure and the expected destination, yet at times runs the risk of losing itself for a few moments on the twists and turns of the unpredictable path. For the journeys that have to be made every day between clearly defined places, such a loss of orientation would be quite unsettling. But on the wanderings to which the adventure of listening leads, such moments of astonished pause are not only permitted but desirable; for it is precisely in them that human travel is condensed into a state of happiness that can no longer be measured in time.

Author: Alexander Honold