Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss were contemporaries. They met in Leipzig in 1887 and remained friends until Mahler's death in 1911. Both Strauss's Zarathustra and Gustav Mahler's Wunderhorn Lieder were largely composed in the years following this meeting in Leipzig. The pairing of Mahler's orchestral songs and Strauss' symphonic poem in one concert is, at least historically, obvious.

But as much as there are similarities between the two composers, there are also many differences. Mahler's works from the last decade of the 19th century form a coherent whole. Two of the Wunderhorn songs appear in his Second Symphony, two more in his Third Symphony, and one Wunderhorn song forms the final movement of his Fourth Symphony. Richard Strauss, on the other hand, composed one work after another. Before Zarathustra, based on Nietzsche's book of the same name ‘for everyone and no one’ (Nietzsche), he composed the tone poem Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, which is about a medieval prankster from Lower Saxony. While Mahler transformed folk songs into advanced art in his Wunderhorn songs, Strauss translated a complex philosophical treatise into rousing orchestral music in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Their posthumous lives also separate the two more than they connect them: while Mahler's music was praised by Theodor W. Adorno as a successful combination of the higher and the lower (‘The unelevated lower is stirred into high music like yeast’), Adorno accuses Strauss of having ‘the manner of an idealised industrial magnate’ who sees the art of composition merely as a craft to be mastered.

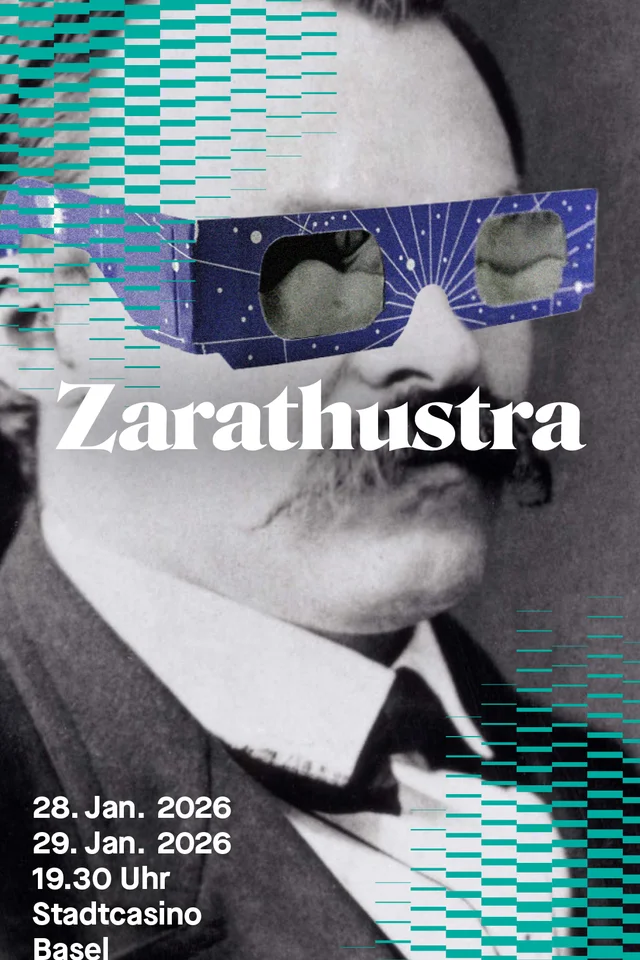

Yes, Strauss understood his craft and mastered the orchestra's sound with a virtuosity few others could match. It is no coincidence that the beginning of Thus Spoke Zarathustra is one of the most famous moments in classical music: a signal-like motif rises three times from an indefinable background: C-G-C. Via C minor, C major and F major, it returns to a radiant C major in fortissimo. But virtuosity in orchestration is never an end in itself for Strauss; it serves to clarify. This is proven by the continuation of this iconic beginning: after the radiant C major tutti, the organ remains alone and envelops the listeners in a humble, church-like atmosphere. After a general pause, the low strings hesitantly sound in pianissimo with a melody, tremoloing and with mutes. Here, as in the corresponding chapter in Nietzsche, we are with the ‘behind-worlders’. After the heavenly sunshine of the beginning, Strauss leads his prophet Zarathustra through a sacred sound space ‘down’ to the common people.

In his Wunderhorn songs, Gustav Mahler does not grapple with Nietzsche, but with simple folk song lyrics from the collection of the same name, Des Knaben Wunderhorn. It was published at the beginning of the 19th century by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano: 723 short songs and poems from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. Mahler quotes the musical horizons of his folk-oriented protagonists: simple dances, folk melodies, lullabies, marches.

As in Tamboursg’sell, for example. The protagonist is sentenced to death. Marching drums evoke an oppressive emptiness. Despite considerable instrumental effort (brass, low woodwinds and low strings), the lamenting drummer remains strangely alone. Only from the middle of the song, when he bids the world “good night” once and for all, do longer melodic arcs extend, which also seem to unite with the singing voice. The familiar musical symbols (marching rhythms, fanfare-like brass) sound neither solemn nor military here, but hollow and abysmal: a dance of death instead of a military parade. This is probably what Adorno meant when he wrote of “yeast” stirred into high music. Mahler composes with the familiar and makes it his own: the monotonous march rhythm is transformed into a general statement about the finiteness of human existence.

Despite all the differences between Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Mahler's Wunderhorn songs, there are certainly similarities. Both works combine the avant-garde with the popular, and in both abstract ideas are found alongside the everyday. Seen in this light, Strauss and Mahler were concerned with the same problem. Namely, how the musical means of the 19th century could be transformed into the freedom that the 20th century seemed to promise. Although rooted in the world of old major-minor harmony, their music has a different aspiration: to musically reconcile the world and the individual, worldliness and transcendence.

Author: Jaronas Scheurer